Why do women get their periods? A handful of species on Earth share a seemingly rare and enigmatic trait: the menstrual cycle. Humans are among this select group, along with certain monkeys, apes, bats, and possibly elephant shrews. What sets us apart is not only that we menstruate but that we do so more frequently than any other species. Despite being a nutrient-draining and physically inconvenient process, menstruation persists. So, what is the purpose of this uncommon biological phenomenon?

To understand the answer, we must start with pregnancy.

Pregnancy is a remarkable process where the body meticulously allocates resources to create an optimal environment for a developing fetus. It is a biological marvel that allows a mother to nurture her offspring within a carefully engineered internal haven. However, this process also reveals an inherent conflict: pregnancy places the mother and her fetus at odds with each other.

The root of this conflict lies in evolutionary biology. The human body has evolved to maximize the propagation of its genes. For the mother, this means striving to provide periods equally for all her offspring, ensuring the survival and reproduction of as many as possible. However, a fetus carries not only the mother’s genes but also those of its father. Paternal genes may favor extracting more resources from the mother to ensure the survival of this particular offspring, even at the potential expense of the mother’s well-being or her ability to care for future children. This creates a biological tug-of-war between maternal and fetal interests, played out in the womb.

One of the key players in this evolutionary conflict is the placenta. The placenta is the fetal organ that connects to the mother’s blood supply, nourishing the growing fetus. In most mammals, a layer of maternal cells forms a barrier that limits the placenta’s access to the mother’s blood periods. This barrier allows the mother to regulate nutrient delivery to the fetus. However, in humans and a few other species, the placenta goes a step further. It invades the mother’s circulatory system, directly accessing her bloodstream to draw nutrients more aggressively.

Through the placenta, the fetus releases hormones that manipulate the mother’s physiology to secure its survival. These hormones can increase the mother’s blood sugar, dilate her arteries, and raise her blood pressure—all to ensure a steady supply of nutrient-rich blood. This direct access makes pregnancy in humans a uniquely high-stakes endeavor. Unlike many mammals that can reabsorb or expel embryos if conditions aren’t favorable, human pregnancies carry significant risks. Once the placenta establishes a connection to the mother’s blood supply, severing it can lead to severe complications, including hemorrhage.

If the fetus develops poorly or dies, it can jeopardize the mother’s health. Even a viable fetus’s demand for resources can cause issues like extreme fatigue, elevated blood pressure, gestational diabetes, and preeclampsia. These risks highlight that pregnancy is not only a profound investment but also a potentially hazardous one. This is why the body employs rigorous screening processes to ensure only the healthiest embryos proceed.

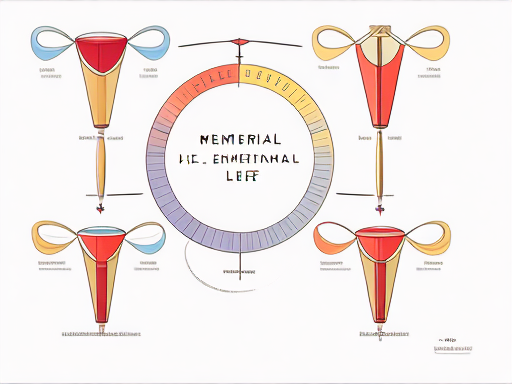

Here is where menstruation comes into play. The process begins with implantation, where an embryo embeds itself in the endometrium—the nutrient-rich lining of the uterus. Over time, the endometrium has evolved to make implantation difficult, effectively testing the embryo’s viability. Only the healthiest embryos, capable of passing this biological test, survive and develop. This selective pressure also led to embryos evolving more invasive and robust mechanisms for implantation, creating an evolutionary feedback loop.

The embryo engages in a highly coordinated hormonal dialogue with the endometrium to facilitate implantation. However, not all embryos pass this test. Some fail to embed properly, and others may begin the process but ultimately falter. These unhealthy embryos pose significant risks. As they die, they can leave the mother vulnerable to infections or release hormonal signals that disrupt her tissues periods. To mitigate these risks, the body has developed a mechanism to eliminate any potential threat: shedding the endometrial lining entirely.

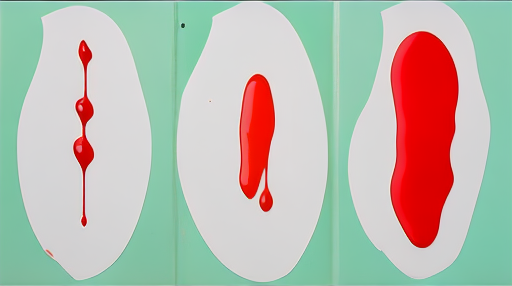

This is menstruation. If ovulation does not result in a viable pregnancy, the uterus expels its endometrial lining along with unfertilized eggs and any non-viable or dead embryos. This thorough cleansing ensures that the reproductive system resets, readying the body for the possibility of a healthier pregnancy in the future. Despite its nutrient cost and physical discomfort, menstruation serves as a vital protective mechanism, reducing the risk of infection and ensuring that only robust embryos have a chance to develop.

In this light, menstruation is not merely a quirk of biology but a pivotal adaptation that safeguards maternal health and improves reproductive success. This process, unique to a select group of mammals.